In the fog of history, it’s easy to imagine the American Civil War as a purely domestic conflict — a bitter struggle confined to North America. But the reality was far more global. The Confederate States of America (CSA) not only fought on the battlefield but also waged an equally crucial war in the drawing rooms of European power. Both Britain and France, dominant global powers in the 1860s, hovered on the edge of recognising the Confederacy — a move that could have changed the course of history and redrawn the map of the modern world.

The Economic Entanglement

The primary bond between Britain, France, and the Confederacy was King Cotton. The Southern states supplied the raw cotton that fed the great textile mills of Lancashire and Normandy. When the Union blockade tightened around Southern ports, the flow of cotton dried up, throwing tens of thousands of British and French workers into hardship. The so-called Cotton Famine led to food shortages and unrest, making Confederate diplomacy seem more tempting by the month.

Confederate agents in Europe — men like James Dunwoody Bulloch and Charles Prioleau (whose Liverpool mansion still stands as a testament to this clandestine war) — worked tirelessly to win recognition, building warships and lobbying Parliament and Emperor Napoleon III’s court alike.

The Trent Affair and the Path to War

In 1861, the Union’s seizure of two Confederate diplomats from a British mail ship, the Trent, brought Britain and the Union to the brink of war. The British government, outraged by the violation of neutral rights, readied troops in Canada and warships in home waters. Recognition of the Confederacy seemed only a whisker away as London demanded the envoys’ release.

Lincoln’s administration, recognising the peril, defused the crisis with the quiet return of the diplomats. But the episode demonstrated how fragile neutrality was — and how a single spark might have ignited a transatlantic war.

France’s Ambitions and Britain’s Hesitation

Napoleon III, ever eager to expand French influence, was openly sympathetic to the Confederacy. He hoped that a divided United States would leave France free to dominate Mexico and the wider hemisphere. France pushed for European mediation, but Britain hesitated. Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and Foreign Secretary Lord Russell were wary of getting entangled in a bloody American conflict, especially one increasingly framed around the issue of slavery.

Ultimately, the Union’s military victories at Antietam and elsewhere, combined with Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, made recognition politically untenable. Supporting a slaveholding nation was too unpalatable for the British public, despite the economic pain of the cotton shortage.

A Different World?

Had Britain and France recognised the Confederacy — or worse, entered the war on its side — the United States might have splintered permanently. The history of democracy, civil rights, and empire would have taken a very different course. It’s a tantalising what if for historians and novelists alike.

For readers fascinated by this hidden international dimension of the Civil War, I explore these very themes in my historical fiction novels:

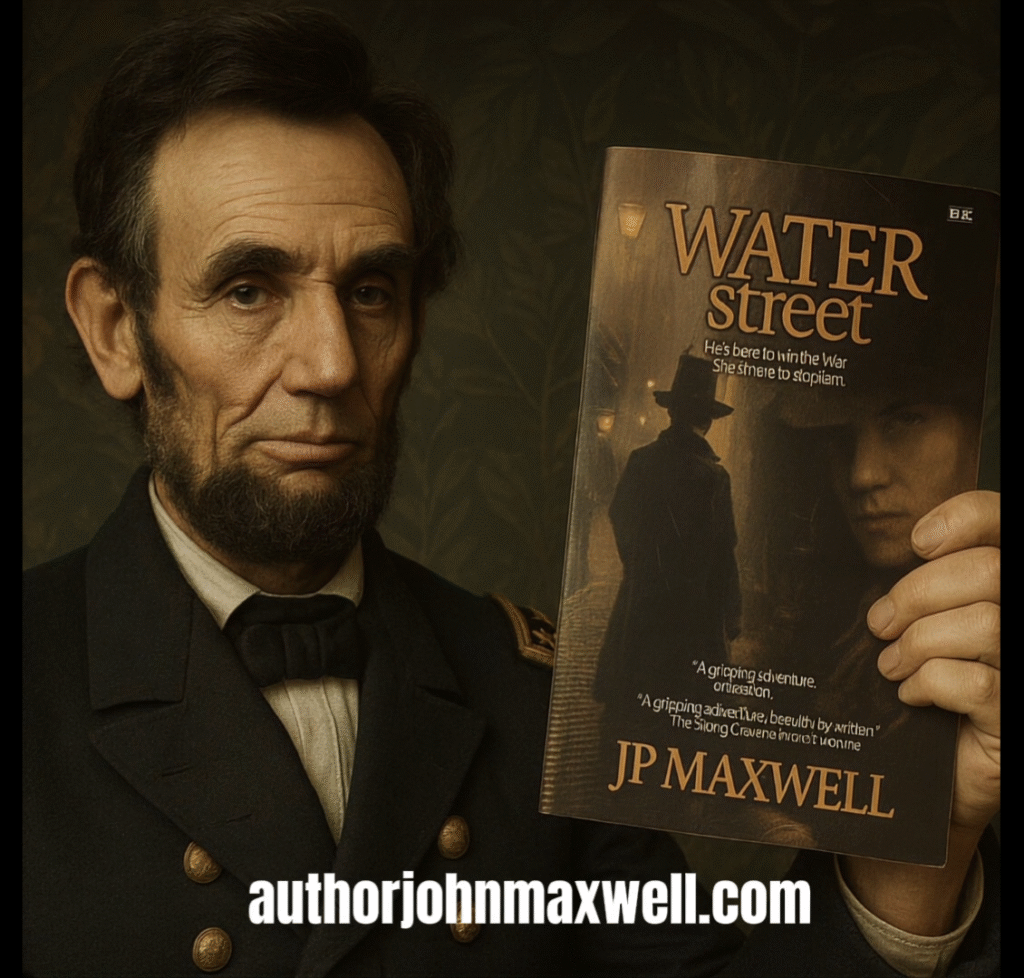

👉 Water Street – A gripping tale of Liverpool’s shadowy ties to the Confederacy.

👉 The Americans of Abercromby Square – A novel of spies, merchants, and politics as Liverpool walks a dangerous tightrope between North and South.

www.authorjohnmaxwell.com

Both novels bring to life the intrigue, danger, and moral complexities of this transatlantic struggle.

#HistoricalFiction #AmericanCivilWar #ConfederateNavy #LiverpoolHistory #19thCenturyHistory #CivilWarNovels #AlternativeHistory #WaterStreetNovel #AbercrombySquare #HistoricalThriller #BritainAndTheConfederacy #NavalHistory #Lincoln #JamesBulloch #CharlesPrioleau #CivilWarDiplomacy #WhatIfHistory #HistoricalIntrigue

American Civil War diplomacyConfederate navy in LiverpoolJames Dunwoody BullochCharles PrioleauCivil War cotton famineBritain France Civil War

The Americans of Abercromby Square https://amzn.to/4jUPshu

The American Civil War Museum: https://acwm.org/

The British Library Civil War Service: https://www.bl.uk/learning/timeline/item103597.html